Every once in a while someone says something that challenges you to the core and forces a rethink of what you thought to be real and true. One such moment occurred for me recently when a friend offhandedly remarked that a mutual acquaintance of ours doesn’t believe mental illness exists.

How bizarre, I thought at the time. How old fashioned. How ill-informed they must be to not believe in mental illness, as if it were nothing but a personal choice like believing in fairies, or the Paleo Diet, or a higher spiritual power. But in the days since, the idea has niggled at me. Having spent three-years searching for a solution to the mental health crisis for my project My Year of Living Mindfully, I’m now buried in a new project about preventing mental illness from childhood, and I couldn’t help but wonder how anyone could dismiss something that’s so… well… right now in our mid-pandemic world?

I mean, jeez, have they not heard all the celebrities now openly discussing their trauma, anxiety and depression? Have they never known someone in the grip of addiction? And if we’re not in the midst of a mental health crisis, then what problem are governments all around the world now throwing record sums of money at to try and fix?

How could anyone really, I mean really believe that mental illness doesn’t exist?

These questions were like splinters in my mind, nagging away at me until I relented and committed to one of my several-day long journalistic deep dives. And I was stunned to discover that there’s actually a very real and very well informed debate among some of the most respected psychological experts in the world as to whether mental illness is actually real.

Most surprising was discovering a profile in Wired, in which the guy who literally wrote the book on mental illness, Professor Allen Frances, confessed, “there is no definition of a mental disorder. It's bullshit. I mean, you just can't define it.”

Frances, who is Chairman Emeritus of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences at Duke University School of Medicine, was the lead editor of the fourth edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which is essentially the mental health profession’s equivalent of the Bible. In 2010, prior to the publication of the most recent edition, DSM-5, Frances went rogue. “We're taking every day experiences that are part of the human condition and we're over-diagnosing them as mental disorders, and way too often providing a pill when there's not really a pill solution for every problem in life,” he told the Cochrane Australia podcast, The Recommended Dose.

Frances’ criticisms were further bolstered in 2019, when researchers from the University of Liverpool conducted a detailed analysis of five key chapters in the DSM-5 on schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and trauma-related disorders and concluded that “although diagnostic labels create the illusion of an explanation they are scientifically meaningless and can create stigma and prejudice.”

Another leading advocate of the mental-illness-isn’t-real camp is clinical psychologist Lucy Johnstone. In a 2019 article for the Institute of Art and Ideas she wrote that it’s not that the torments of our mind we currently label “mental illness” aren’t real – anyone who’s known suicidal despair, heard hostile voices, experienced crippling anxiety or mood swings will tell you the misery is very very real. Rather, she argued, these experiences are not an illness.

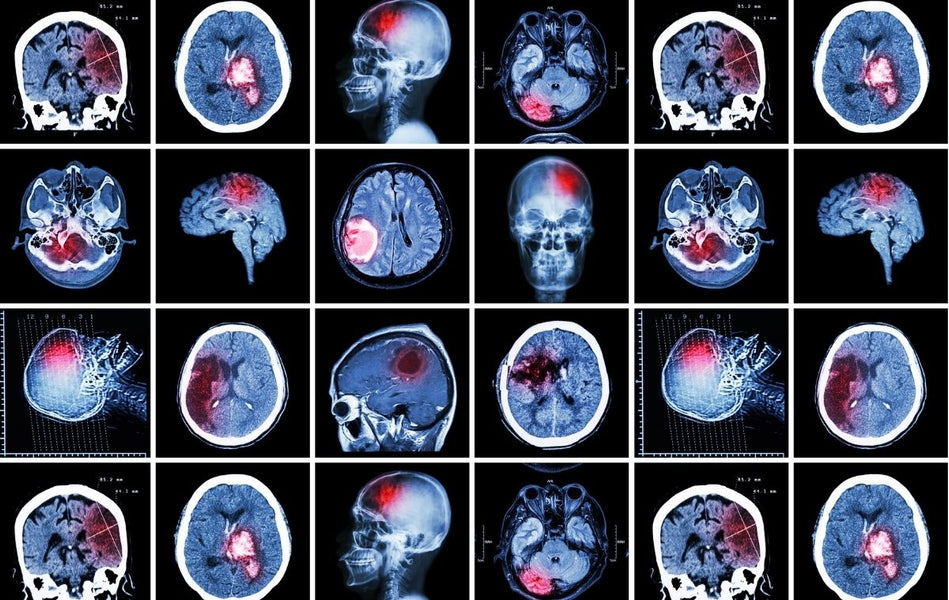

Johnstone highlights that unlike with diseases such as pneumonia, liver failure or breast cancer, there are no established patterns of chemical imbalances, genetic flaws or other bodily malfunctions which directly correspond to the labels and symptoms of what we call mental illness, despite decades of research. “If we ask ‘Why does this person have mood swings/hear hostile voices?’ the answer is ‘Because they have ‘schizophrenia/bipolar disorder’. And if we then ask how we know they have ‘schizophrenia’ or ‘bipolar disorder’, the answer is: ‘Because they hear hostile voices/have mood swings.’ There is no exit from this circle via a blood test, scan or other investigation which might confirm or disconfirm this diagnosis,” she wrote.

Even the pharmaceutical industry now concedes that the “chemical imbalance” explainer for mental illness, which was first popularised in the late 1980s alongside marketing campaigns for prescription medication such as Prozac, is oversimplified and inadequate.

At a 2015 event hosted by Intelligence Squared, which asked panelists to debate if “psychiatrists and the pharma industry are to blame for the current ‘epidemic’ of mental disorders”, the former senior Vice-President and Head of Worldwide Drug Development at Pfizer, Declan Doogan, acknowledged that selling drugs using the biological model of mental illness was a mistake. “There’s no blood test for depression and nobody’s said we’ve found the cause for it. We don’t actually mean that if we give an SSRI, your problem is serotonin deficiency. That was a naive and simplistic view put forward many years ago,” he said.

Doogan’s debate team ultimately persuaded the audience 52-46 percent that the Big Pharma did not intentionally create the epidemic of mental disorders (with 2 percent undecided), but his concession shone a whole new light on the chemical imbalance story that was sold to me in my teenage years and young adulthood in the late 1990s and 2000s; a time when the anti-depressant medication Zoloft was being prescribed to almost every emotionally distressed person I knew and was the sixth best selling pharmaceutical in the U.S.

It turns out, despite the mass media’s popularisation of the concept, there has never been a single peer-reviewed study to directly support claims that chemical deficiency is the cause of any mental disorder.

This is not to say that there aren’t biological signatures for people experiencing inner misery. There is robust evidence, for example, that childhood abuse and neglect results in permanent changes to the developing human brain. But as Professor Richard Bentall from the University of Sheffield argues in a 2019 panel discussion hosted by the Institute for Art and Ideas, everything is biological. “The temptation has always been to say, we’ve got something going on in the brain scanner, that means it’s a biological illness, it doesn’t mean anything of the sort…. What’s going on is their brain is responding to events in the world. So where is the cause of the mental illness? I’d say it’s the events in the world and the brain is a, what we’d call… a mediator.”

Although Bentall may not be a household name, he’s been enormously influential in modern psychology, having authored more than 200 peer-reviewed academic papers, conducted large scale randomised controlled trials of psychological interventions for people diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and psychosis, as well as written a number of books including, Madness Explained: Psychosis and Human Nature and Doctoring the Mind: Is Our Current Treatment of Mental Illness Really Any Good?

His conclusion, after more than three decades of research? “What we should be wary of is seeing these phenomena as medical phenomena, which require medical intervention rather than responses to a world which is challenging and difficult to live in and difficult to navigate our way through,” he told the Institute for Art and Ideas panel.

Most recently Bentall’s research has focused on why childhood adversities such as poverty, abuse, and bullying provoke the mental and emotional changes that lead to what we call mental illness. He’s found that a child who experiences a significant traumatic event before the age of 16 has a three times increased risk of psychosis in adulthood and that there’s a dose response relationship – the more severe the trauma, the greater the risk of psychosis.

All this is to say, I’m now coming to more deeply understand that our very real mental anguishes – from our persistent low moods, to our social neuroses, to our compulsions to use substances that do us more harm than good – could be seen not as diseases or illnesses, but as understandable, natural, normal responses to life’s adversity.

Viewed through this lens, the rise in environmental anxiety among our teenagers is a reasonable response to a very real threat. The disproportionally high suicide rate in Aboriginal Australians is an understable outcome of hundreds of years of intergenerational trauma. And increases in tech addiction and social disconnection? A natural relationship with devices engineered to get us hooked. Perhaps it’s not that we are sick. It’s that the world in which we live is sick. Or, as Bentall said recently in an interview for the BBC Radio podcast, The Life Scientific; “madness is in the world, not in us.”

Somehow I don’t think any of this is going to catch on meaningfully in mainstream mental health policy and reporting any time soon though. A headline screaming that “Six Out of Ten People Have Perfectly Reasonable Anxiety Response to Pandemic Related Lockdowns and Sudden Financial Instability…” won’t generate the click-traffic that online editors need in order to meet their KPIs. But all this will significantly reshape the direction of the work I do in the future.

Although I still think there’s great utility in having widely accepted concepts of mental illness, and that efforts to destigmatise our suffering must continue; although I will also continue to advocate for mental health workers on the frontline who need more and urgent support; and although prescription pharmaceuticals prescribed in the right circumstances, at the right time, have saved the lives of people I love; I now also see that the real solutions to our collective mental distress will likely found when, in addition to helping individuals who are suffering, we start making meaningful efforts towards understanding and treating the root causes of that suffering.

Perhaps one of the most striking studies I came across during my latest deep dive was done by researchers from Public Health Wales and Bangor University, who knew that men in prison are at increased risk of poor mental health and suicide and wanted to know why. They interviewed hundreds of men imprisoned in Bridgend, South Wales and found 84 percent of them had experienced at least one Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE), compared with the Welsh average of 46 percent. Nearly half of the prisoners (46 percent) reported they had experienced four or more ACEs such as abuse, neglect, domestic violence, or parental drug and alcohol addiction, compared to 12 percent in the wider population.

Knowing all this now, I can’t help but wonder if we could do more to help people by better understanding the steps that lead from childhood misfortune to mental illness? And what would happen if the events that shaped those men, who committed those crimes, that put them in that prison, never happened in the first place?

I'll leave you with words of award-winning mental health activist Doctor Eleanor Longden, who’s TED talk about her personal experiences with voice hearing has been viewed more than five million times, and who was once told by a psychiatrist that she’d be better off with cancer than schizophrenia, because cancer is easier to cure; “...the most important question in psychiatry shouldn’t be what’s wrong with you, but what’s happened to you.”

If you or someone you know needs help:

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Beyond Blue: 1300 22 4636

Headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation: 1800 650 890

The Connection (DOWNLOAD-TO-OWN)

The Connection (DOWNLOAD-TO-OWN) My Year Of Living Mindfully - Book

My Year Of Living Mindfully - Book