It had been 20 minutes of mental agony and as my meditation practice came to an end on the third day of what was supposed to be a year-long commitment to meditate every day, there was only one thought on my mind… it’s going to be a long year.

Was I missing something? Far from being “like a bubble bath” for my mind in order to “fight stress,” “think better” and “feel happier,” I was finding mindfulness training really difficult and rather unpleasant. No sooner did I follow the teacher’s instructions to direct my awareness to a point of focus (be it my breath, my body, or whatever else) than I found my mind was elsewhere. Thinking, planning, remembering… anything but where I was intending it to be.

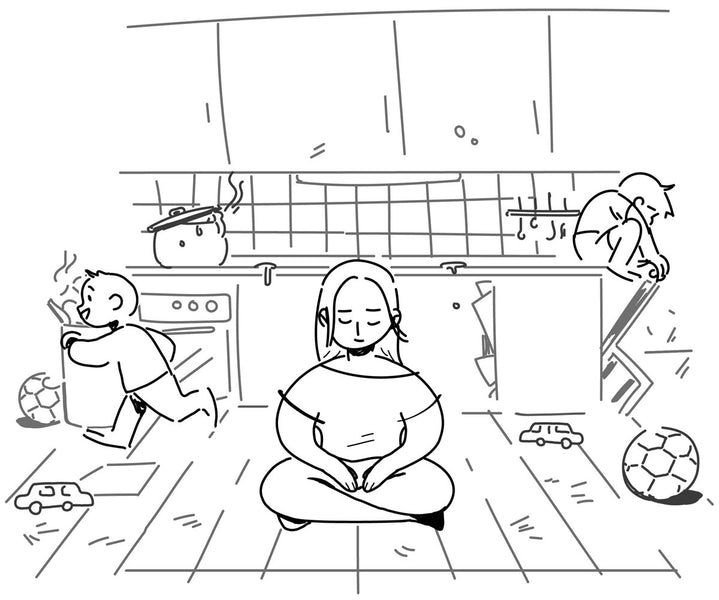

As I described in my subsequent film and book My Year of Living Mindfully, Buddhists describe this mental training technique as like taming a “monkey mind,” but for me, it was more like trying to wrestle with a bull elephant. In fact, the hardest thing about my latest project wasn’t convincing 18 world-leading mindfulness experts to give me advice, or lining up a team of scientists to donate their time toward studying me for a year. It wasn’t even cancelling 150 screenings and pivoting to an online release in the middle of a pandemic, while in lock down and home schooling two small children. Nope… the hardest thing about my year of living mindfully was… actually living mindfully.

I’m not alone in finding it difficult to stick to my well-intended plans to live healthier. Fewer than one in five of us report being successful in our goals to lose weight, start a regular exercise program, eat a healthier diet and reduce our stress. Among those who study behaviour change, this universal phenomenon is known as the intention–behaviour gap. It turns out, even really really really wanting to change, or having very good reason to stick to a healthy living plan doesn’t mean we actually do.

One study showed that in an age of personalised medicine, where we can have our DNA analysed to tell us how likely we are to get certain diseases, having this knowledge wasn’t enough to motivate people to change their behaviour. Another study found that only 10 percent of people who’d had surgery after a life-threatening heart attack were able to maintain healthy diet and exercise changes and adhere to their medication. A similar effect is seen in people with other illnesses too, where on average about half of patients with chronic diseases don’t comply with their medical prescriptions.

It’s not that we’re morally deficient, fundamentally flawed, or weak-willed. It’s that the odds are against us. This is an era where spending on junk food advertising is nearly 30 times greater than the government spend on promoting healthy eating, a time when “if you snooze you lose” is a mantra promoted by leaders many revere, and when one in five parents working full time is putting in five extra weeks a year in unpaid work, just to keep up with the demands of the job.

When I embarked on my year of living mindfully I knew I needed more than willpower to get me through. So I turned to the work of Professor Peter Gollwitzer, from New York University, who has spent decades studying methods for overcoming the intention-behaviour gap.

Over the years Peter has developed and refined a simple technique called the If-Then planning which is proving to be remarkably effective. Because around 50 percent of what we do every day is not actually driven by our conscious thought, but by our unconscious instincts, patterns, and behaviours my theory behind using an If-Then planning strategy was to automate my mindfulness practice. (Lets face it, with a never ending feed of dream indoor plants walls on Pinterest and heroic Highlanders to catch up with on Netflix, I needed a serious help to stick with my meditation goal during my rare moments of down time.)

If-Then planning involved specifying:

These days, my If-Then planning has evolved, but it now looks something like this:

A meta-analysis of 94 studies examining the effect of taking this approach showed a significant impact on people following through with their intentions. As I wrote in my free resource, A Beginner’s Guide to Starting a Mindfulness Practice, it turned out to be one of a number of key strategies I used throughout my mindful year.

It’s now day 1184 of what was supposed to be a year-long commitment to meditate every day. I still find the practice difficult. I still have trouble focussing my unruly mind. And truthfully, after a long hard day at work, I’d still rather check-out and watch a great TV series than make the effort to train my mind. But, if you've seen the film or read the book that resulted from my year-long effort to meditate every day, you’ll know that there’s a very good reason I’m still at it, day in and day out.

The Connection (DOWNLOAD-TO-OWN)

The Connection (DOWNLOAD-TO-OWN) My Year Of Living Mindfully - Book

My Year Of Living Mindfully - Book